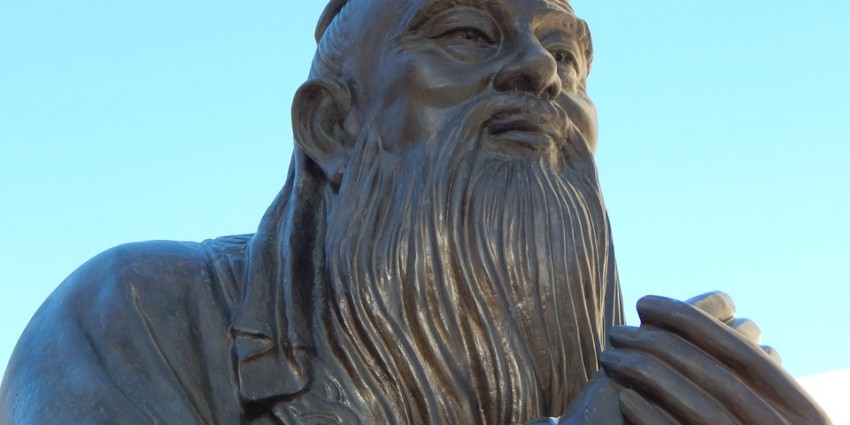

The 2015 visit by Xi Jinping to the United Kingdom raised many issues, but one matter that went unreported was the increased importance of Chinese language learning opportunities for UK students. There has been a recent injection of investment in schools to try to have another 5,000 Mandarin speakers in the country by 2020, while China has become increasingly engaged in the UK’s higher education system. According to Shen Yang of the Chinese Embassy in London, the United Kingdom now leads Europe in the teaching and learning of Mandarin, with 29 Chinese government-backed Confucius Institutes and 127 Confucius Classrooms throughout the country.

My recent Politics article as part of the Special Issue on the Soft Power of Hard States quotes the Director of the Confucius Institute at Ulster University, who noted that the “institute’s activity mainly focuses on the development of Chinese language teaching at all levels of the educational system”. Further to this the Ulster Confucius Institute has 28 teachers across 122 schools, who teach Mandarin to over 6,000 children, which gives an indication of the scope of this programme.

Elizabeth Truss, the UK’s former Minster for Education, has stressed the economic benefits of learning Mandarin. In 2004 she commented that, “China’s growing economy brings huge business opportunities for Britain and it is vital that more of our young people can speak Mandarin to be able to trade in a global market and to develop successful companies”. Confucius Institutes play an important role in this process; what my article does is examine and analyse this impressive programme within the context of China’s soft power campaign.

My article examines Confucius Institutes as an important tool in China’s public diplomacy, employed by the Chinese government to communicate specific strategic narratives about China to foreign publics. In so doing, it also increased China’s soft power around the world. Based on empirical data from Confucius Institutes in different parts of the world, my article demonstrates that the impact of Confucius Institutes is hampered by both political and ideological concerns, as well as a number of practical issues. The article argues that Confucius Institutes’ do not present the ‘real’ China to the world, but rather a ‘correct version’ of it, which in turn limits their ability to project China’s strategic narratives effectively and increase its soft power.

The full Politics Special Issue on the Soft Power of Hard States is available now. Read more in the Politics blog on China’s regime security concerns, the place of conspiracy theories in global diplomacy, Russia’s great power identity, Russia’s unique approach to soft power, Ukrainian responses to Russia’s cultural leadership and the way in which Russia and China use soft power differently.