Those of us who work at South African universities have recently been pushed to think very carefully about our teaching. The rise of student movements like the Rhodes Must Fall movement at the University of Cape Town and the Open Stellenbosch movement at Stellenbosch University insist that South African universities remain anti-black spaces which need decolonisation. The Black Student Movement (BSM) at my own institution, Rhodes University – or, as the BSM describes it, the University currently known as Rhodes University – have drawn attention to the need both for symbolic changes, such as a change in the institution’s name, as well as substantial shifts in order to enable the flourishing of black students. Key among these changes is the question of changing the curriculum and a key question in relation to curriculum change is the question of to what extent and in what way Africa is taught.

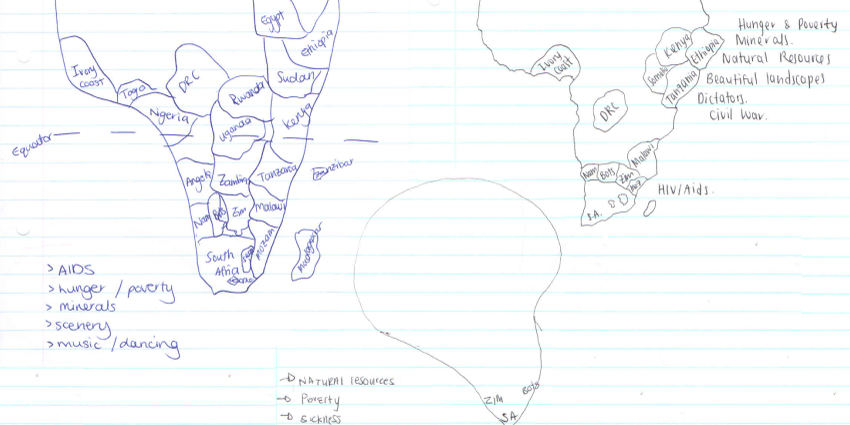

My teaching is mostly in the area broadly known as ‘African Studies’ and so the question of how to teach Africa is one that is constantly on my mind. In my recent Politics article, ‘Reflections on Teaching Africa in South Africa‘, I reflect on the challenges of teaching African Studies, focusing on the particular challenges that arise when teaching African Studies in South Africa. I note that we teach Africa against a backdrop of everything else students have been taught about the continent, or have learnt about it through media and popular culture. But this backdrop is riddled with a range of misrepresentations and unhelpful generalisations which teachers of African Studies have to confront and try to address. To try to figure out what knowledge and ideas about Africa my students bring into the classroom, I recently began one of my courses by conducting an exercise in which students drew a map of Africa, filling in all the countries they knew, and then wrote down the key words they associate with the continent. The results of this exercise, which are discussed in my article, reveal that my students, despite living in Africa, lack knowledge about much of the continent, and have somewhat similar assumptions about the continent to those of Western students.

Given that the study of Africa has been so dominated by Western scholarship and that my students, despite living in Africa, seem to have been very much influenced by the portrayal of Africa in Western media and scholarship, it is tempting to focus my teaching on the presentation of ‘African alternatives’ to mainstream Western discourse on Africa. However, I argue in the article that this strategy ultimately fails both because it is difficult to neatly delineate between ‘mainstream’ and ‘alternative’ approaches to Africa, but also, and relatedly, because the problematic ways in which Africa has been represented tend to infuse even our attempts to overcome them.

My article grapples with what this means for teaching African studies to African students who in many ways – and legitimately so – hunger to be taught something they see to be an alternative to mainstream representations of the continent. My article also grapples with another key topic in recent debates about South African universities – the way in which the post-apartheid academy remains dominated by whites. I teach African Studies at a university where around three quarters of the academic staff members are white. I stand in front of the classroom as yet another white lecturer and my whiteness affects the way in which my teaching about the continent is interpreted by my mostly black students. I reflect on some ways in which I have tried to think through and address this in my teaching of African Studies.

The recent difficult but necessary discussions of transformation and decolonisation at South African universities have once again pushed me to think, re-think and re-think again the way I teach Africa. As I note at the end of the article, teaching about Africa at an institution such as my own is fraught with difficulties, but at the same time I am grateful for the opportunity to engage with very committed, energetic and creative students who are affected deeply by debates about Africa and willing to engage passionately with the course material.

Discussion