Introduction

It is spring 2017, a room full of students with everyone’s head down, pens moving, but none taking notes. There is the burble of conversation and intermittent chortles. These are final year university students and they are all drawing what they understand civic engagement to mean. How did it come to this?

Wait, let’s begin again, earlier, when Myspace was still cool, blackberries were phones, and Alt right was only found on computer keyboards.

The Beginning (again)

After years of asking first year students in their first politics class in university “what is Irish Politics”, and being amazed at how quiet a packed lecture theatre can be for 30 … 45 … even 90 seconds … we knew we needed to change something.

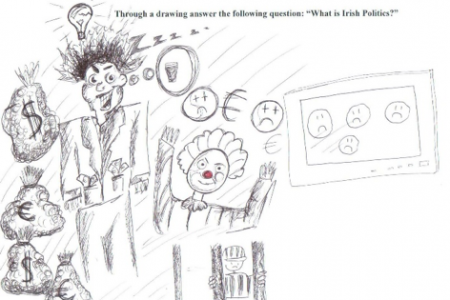

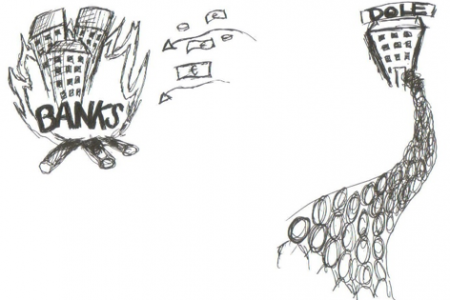

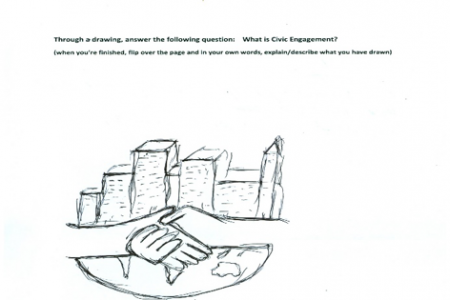

In autumn 2007 we introduced freehand drawing into our first ‘Introduction to Irish Politics’ class of that year. We provided each student with an A4 sheet with instructions on one side stating: ‘Through a drawing answer the following question: What is Irish politics?’ The other side said: ‘Now, in your own words, describe/explain what you have drawn.’ Once the drawings were completed, we divided the class into groups of 5 students to discuss their drawings amongst themselves. That in these groups every voice is heard encouraged interpretations from multiple perspectives. But, it was when each groups’ rapporteur reported the themes that emerged from their discussions, and we record these on the lecture theatre’s projector screen, that the purpose of the class was revealed, and the students realized that they collectively possessed a wealth of knowledge on a topic they struggled verbalise. That they lacked the vocabulary of politics was no longer an issue. By enabling students to draw their own interpretations, they have a visual representation of their thoughts that transcend verbal reasoning and can permit them to access unrecognised insights and make sense of complex issues by employing a whole brain approach.

Collecting the drawings produced after each initial class of the year, every year, over the past decade, we have seen how perceptions of Irish politics have evolved for those aged 18-19 years. They have changed from being positive in 2007 and 2008 to almost uniformly negative between 2009 and 2012, and since 2013 moved back towards positive again. This past September, the first years (who were about 9 years old when the economic crisis struck), created drawings that suggested responsible politicians, a happy citizenry and a strong constitution.

In all, we have collected more than 1,500 drawings since 2007, their changing themes reflecting the changing perceptions of politics among some of our youngest voters. All of the images (see sample below), no matter how artistic, cynical, absurd, or obscene, carry a truth as to how their creators perceive Irish politics.

Back in 2017

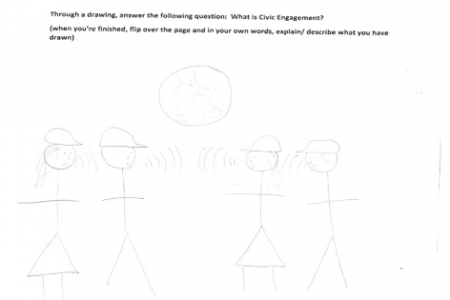

Fast-forwarding to spring 2017, we were using the freehand drawing technique to investigate how final year degree students from the sciences and humanities understood civic engagement, a transdisciplinary topic, to see if there was disciplinary bias (see samples included in this blog). We did this as in recent years, many Irish higher education institutions have reimagined their missions, no longer focusing exclusively on teaching and research, but now embracing a third purpose: developing students’ civic capacity and preparing them to become active democratic citizens.

Freehand drawing and critical pedagogy

As a teaching approach, capable of generating a critically reflective stance, freehand drawings can build students’ ability to engage in critical thinking as well as providing insights into their perceptions. By enabling students to draw their own interpretations, we get a chance to peer through the window of their thoughts.

Introducing critical pedagogy, through use of the visual, necessitates redefining the roles and responsibilities of faculty and students. This is about positioning faculty and students on the same epistemological ground, where everything is contestable. Although often basic and superficial, when we pressed the students in their thinking on interpreting their drawings during the in-class discussion, they began to recognise, and cautiously query, their own and others’ conjectures.

Conclusion

We feel that using freehand drawing, in encouraging students to reflect critically, contributes to developing the kind of engaged citizenry vital for a flourishing and self-critical democracy. By by-passing the need for a refined vocabulary, we gain insights into the complexity of what students understand. The approach also surmounts the long-term bias in instructional pedagogies toward oversimplification and the favouring of propositional knowledge, as it allows students to appreciate that there are many ways to comprehend, contest and analyse issues.