In 2016, Donald Trump unexpectedly won the White House following an anti-elite populist election campaign which emphasised an exceptionalist and nativist view of America’s place in the world. Reviewing the president’s tweets and speeches in the lead up to the 2018 midterm elections, Corina Lacatus finds that Trump’s far-right populist rhetoric now links closely with his administration’s policies, including pursuing a harder, more self-interested line on immigration, US international commitments and trade relationships.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Populism and President Trump’s approach to foreign policy: An analysis of tweets and rally speeches’ published in Politics, as part of the special issue ‘Elections, Rhetoric and American Foreign Policy in the Age of Donald Trump’

This article first appeared on the LSE American Politics and Policy blog.

Donald Trump has been described as the populist par excellence. In the months leading up to the 2016 presidential election, candidate Trump ran a campaign infused with a right-wing populist view of the world. In the absence of a well-developed policy programme, he made promises to ‘drain the swamp’ of American politics, to rid the United States of illegal immigration, and to restore the international respect that the country had lost by agreeing to enter into ‘bad deals’ with long-term allies.

As is common in election campaigns, Trump focused his public communication predominantly on domestic issues, taking positions on foreign affairs only in broad terms and mostly to advance his message on national policies. In the first half of his presidency, Donald Trump has been keen to convince his voter base that he ‘delivered on his campaign promises’ to keep America safe, grow the economy and increase employment. It is fair to expect that, at least to some extent, his public communication as president would echo the messages of his election campaign.

To what extent has the signature populist rhetoric of 2016 presidential hopeful Trump continued to shape President Trump’s approach to policy-making in the years since his victory?

To answer this question, I study the use of populist rhetoric in Donald Trump’s public communication ahead of the November 2018 midterm elections, from rally speeches held during the two months prior and tweets published in the official personal account @realDonaldTrump at the same time. I find that resurgent Jacksonian populism – an early 19th century anti-elitist movement which emphasised presidential power – promoted by the Tea Party’s position shapes President Trump’s approach to both domestic and foreign policy. Fundamentally anti-elitist, Trump’s populism opposes migration, multilateralism, and is deeply sceptical of the United States’ capacity to support a liberal global order that he perceives as detrimental to the economic interest of the American people.

What is a Jacksonian view of the world?

The contemporary rise in support for the Tea Party movement and Donald Trump is best understood as a current form of Jacksonian revolt against misguided and corrupt elites. Inside the Tea Party, two main voices dominate – on the one hand, the inward-looking, neo-isolationist approach advanced by Senator Ron Paul and his supporters (which would see a complete withdrawal of the US from international interventions) and on the other hand, the faction which endorsed 2008 Republican Vice Presidential candidate Sarah Palin and her stronger preference for the United States to win wars rather than withdraw completely from international conflict.

At its core, Jacksonian populism is anti-elitist. More often than not the elites are members of government and the political establishment, i.e. senior party members. The Tea Party has revived Jacksonianism with a particular aversion for those perceived to belong to a liberal, well-educated, and intellectual elite. This antipathy extends also to the international sphere and the institutions that uphold liberal internationalist values, such as the promotion of liberal democracy around the world, any efforts to cooperate through multilateral organisations as well as entering and upholding international treaties. Endorsing a Hobbesian view of the international system, they view the world as a place where states always pursue their own selfish interests and have limited interest in co-operation. In this context, they endorse nationalist and American exceptionalist views and harbour deep scepticism about the ability of the United States to create and uphold a liberal order.

At the same time, Jacksonian populists tend to prefer aggressive militaristic responses to crises around the world, while advocating for trade protectionism and the dismissal of costly alliances and security guarantees. In their eyes, the United States is not meant to be the police of a liberal global order, but war is a necessary response when states violate their international obligations or attack the United States.

A populist president on a perpetual presidential campaign

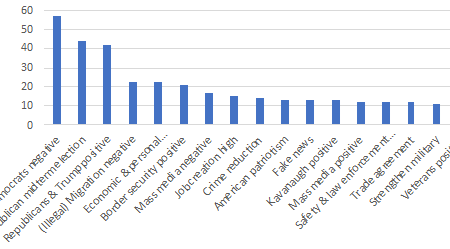

In 2018, Trump’s public engagement with his electorate and the wider public at his rallies and on Twitter echoes the same tone of the official campaign communication in 2016. As Figure 1 shows, virulent critiques of previous administrations and Democratic politicians occur alongside kudos for Republican politicians who have supported the Trump’s administration’s policy initiatives so far and made approving remarks about the activity of the president since his inauguration. Both speeches and tweets communicate to the electorate a clear message, as printed on many rally signs: ‘Promises made; promises kept.’ President Trump is a man of his word, who made guarantees in his 2016 campaign and has made every effort possible to keep them despite opposition by Democrats in Washington. His policies are not only very good, in fact, they surpass the policies of previous administrations and often, are simply the best America has ever seen. Importantly, his policies are the only ones motivated solely by the best interest of the American people.

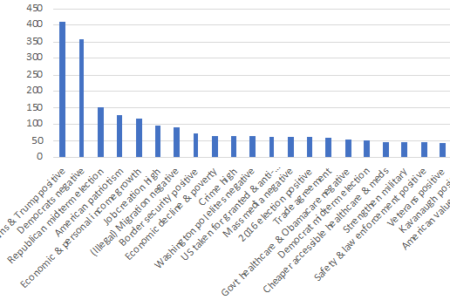

Figure 1 – Coded themes in Trump’s tweets (over 10 references)

In his speeches (Figure 2), the ‘American people’ is synonymous with disenfranchised workers from the Midwest and the South, who have suffered from lower incomes and loss of employment due to globalisation, job flights, and bad trade agreements signed by previous administrations. To correct mistakes from the past, Trump has imposed new tariffs on European and Chinese goods and has entered a new continental trade agreement, the UMSCA, with Canada and Mexico. He cites higher employment rates to demonstrate the success of his efforts to protect the rights of workers in agriculture, manufacturing, as well as the steel and aluminium industries. To secure employment and benefits for American citizens, Trump considers border security and strict immigration controls to be essential. Illegal migrants are malevolent, criminals, and a direct threat to the employment and public services paid for by American workers. He is also particularly concerned with the wellbeing of veterans and of the active members of the military, seeking to make healthcare and other public services readily available to them.

Figure 2 – Coded themes in Trump’s speeches (over 40 references)

Trump says no to the liberal internationalism of his predecessors

What sets Trump apart from all other presidential candidates in 2016 was his aggressive dismissal of liberalism and, with direct foreign policy implications, also of liberal internationalism. In his eyes, the democratic norms and multilateral institutions that support the liberal international order are fundamentally flawed because of the economic and financial imbalance they generate. By 2018, Trump’s approach to foreign policy had crystallised further. He views a world order that relies on a greater financial commitment and stronger military support from the US as essentially unfair and exploitative. Trump presents such a change in international position as directly relevant to his voter base, guaranteeing increased economic prosperity and greater pride in their nation’s ability to garner international respect. Trump does not appear interested in the promotion of human rights abroad, or the promotion of democracy tied to foreign aid and international development efforts. In fact, he derides international financial assistance as a form of exploitation to which the US has fallen victim due to poor foreign policy agendas of previous liberal administrations. In his public communication, his international political affinities lie primarily with far-right political figures, such as the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro and the Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

In line with far-right populist discourse, Trump advances an exceptionalist and nativist view of America’s position in the world in his tweets and rally speeches from 2018. Trump’s official rhetoric centres on the need to immediately remedy three main areas of foreign policy concern – renegotiating existing trade agreements with principal trade partners, strengthening American’s military position in the world, and curbing illegal migration. Trump frames his main role as president in populist terms. His experience in the area of international business is essential to correct mistakes made by previous administrations, who have signed ‘bad policies and agreements’ and have allowed other leaders around the world to take the United States for granted. Subsequently, the United States is in the position of a victim of disadvantageous agreements, due to which it has suffered economic decline and significant job loss. To paraphrase him, America has regained the international respect of which it is worthy. Importantly, this respect translates directly into more jobs and higher incomes for the American people.

Trump’s consistent anti-immigrant and pro-border security rhetoric

Two of the most important themes in his official communications both in 2016 and in 2018 are the border security and, relatedly, of immigration control. These two policy issues lie at the centre of Trump’s public discourse of a distinctly populist nature, with important ramifications for both domestic politics and foreign policy. Domestically, Trump presents illegal immigration as a threat to the physical security of the American people, as migrants crossing the border from Mexico are often violent criminals. Once settled in the US, they are likely to be taking jobs away from American citizens and are thus a greater threat to Americans’ job security and personal wealth.

As a foreign policy concern mentioned in rally speeches, Trump often addresses the Mexican government and also other Central American administrations calling them to intervene with force to put an end to what he calls ‘the caravans’ of illegal immigrants consisting mostly of refugees from El Salvador and Honduras that travel through Mexico in hopes to reach the US. Trump does not stop short of threatening to commit military force in response of illegal attempts to cross the southern border of the US. To him, refugees are migrants who choose not to enter the US legally and who aim to take unfair advantage of benefits made possible through the hard work of American taxpayers. Moreover, Trump blames the liberal Democrats for being supportive of illegal migration and focusing on refugee rights protection. He blames liberals for jeopardising the security of the American people by intending to build ‘sanctuary cities’ that welcome migrants and to squander away public money to offer illegal immigrants access to public services. Worst of all, in Trump’s eyes, is the Democrats willingness to grant illegal migrants the ultimate right of all, to become American citizens and gain the legal right to vote.

Trump’s populist rhetoric pervades

One of the most remarkable, indeed shocking, aspects of the Trump presidency is his rhetoric. His manner of communicating with the public about his activities, policies, and the everyday is unprecedented in the White House. Trump’s regular use of social media, with its immediacy of contact, also makes communication feel spontaneous and authentic. Trump’s public discourse engages with themes pertaining to populism – he speaks against the elites while professing to represent the best interest of the American people. A staple of the electoral campaign of 2016, this type of populist rhetoric continued after Trump’s inauguration and has since spilled over into the practice of foreign policy-making.

A revived Jacksonian populism infuses Trump’s ‘America First’ approach to foreign policy. He harbours disdain for liberal elites and their ideals for international cooperation, multilateralism, and a global liberal order. Moreover, President Trump appears no longer interested in fostering old economic alliances, which he views as ‘bad deals’, and seeks to renegotiate new trade deals that he finds much more favourable to increase the wealth and well-being of the American people. Importantly, Trump’s rhetoric shows a deep scepticism for the United States’ capacity to continue maintaining a liberal order. Rather, in his eyes, a disgruntled America has found itself entangled in a great number of unprofitable international alliances from which it needs to reclaim its sovereignty. In this context, Trump’s use of populist rhetoric allows him to explain the main goals of his foreign policy through direct ties with domestic priorities he identifies as being of utmost import to the American people – job creation, economic growth, and border security. Ultimately, Trump claims to have begun the important process of restoring the long-lost international respect for the US as a global economic and political power.